Ancient Egyptian Mummies

An overview written by Michael E. Habicht, Egyptologist, May 2015

Introduction

The word mummy comes from the Persian

‘mumia’, describing natural bitumen which was used in ancient Egyptian

mummification and was a highly desired ‘medical’ powder, used for

multi-purpose medicine since the middle ages. Still in 1924, mumia vera

aegyptiaca was available in a German pharmacy price list.

Since the 18th century it

became a fashion for travellers to bring a mummy and a coffin to Europe

and overseas as an exclusive souvenir, and to unwrap it around midnight

as a party gag, searching for precious amulets. Scientific interest

began somewhere around 1834, when the British doctor Thomas Joseph

Pettigrew published a book on his examined mummies.

- Papyrus on the body of Neskhons. Copyright: IEM 2011

What is a mummy?

A mummy is a dead body, human or animal, preserved from decaying by special environmental condition (permanent frost, dry and hot climate, peat bogs) or artificially treated with substances. The natural mummies are preserved by coincidence, the most famous one is the man from the Hauslabjoch (aka „Ötzi“) or bog bodies from northern Europe (Tollund Man). Artificial Mummies are known from different time periods all over the world. The Egyptian mummies are well known, but there are also Chinese ones, like the famous Xin Zhui, the Marquise of Dai, who died about 160 BC and is still preserved almost undecayed, Pre-Columbian mummies of South America, The mummies in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo etc. Also some modern VIP’s of our age are mummified: Lenin, Mao Zedong, Eva Perón, Kim il-Sung, Kim Jong-Il.

Mummification stops natural putrification

Shortly after death, a chain reaction starts, leading to decomposition of the body. Thereafter bacteria start devouring the body. Mummification stops this reaction. Different taphonomic conditions lead to mummification. In dry and hot areas, dehydration leads to the death of bacteria and the process of decomposition stops. In extreme cold conditions chemical processes will slow down and in peat bogs, an almost completely anaerob condition and bog acids prevent the body from decomposition. Treatment of the body with embalmingresin and bandages helps to protect the body against bacteria, microbes and flies.

Motivation for mummification in Ancient Egypt:

People in Ancient Egypt believed in an immortal soul, the human being consists of several parts: Body, Shadow, Name and three soul aspects: Ba (free floating soul) Ka (life force) and Akh (dead spirit which the dead becomes after death). The Ba must be able to return to the mummified body. They were preserved by removing the viscera, and treating the corpse with natron salt (a natural salt mixture found in Wadi Natrum and El-Kab). Natron (natriumhydrogencarbonate & natronbicarbonate) has a powerful dehydrating effect. The viscera, sometimes in high quality mummification, have been separately mummified and stored in canopic jars.

Short overview on mummy research

Shortly after the discovery of X-ray radioation, Conrad Roentgen started x-raying mummified tissue. The discovery of two royal cachettes in 1881 (Deir el-Bahari tomb 320) and 1898 (Valley of the Kings tomb 35) and other findings saved for science a highly important collection of Pharaohs of the New Kingdom and of the High Priests and their family members of the 21st Dynasty. Grafton Elliot Smith made the first autopsies on the royal mummies and published them in 1912. The publication is still of high value for science. About the same time, in 1907, British Egyptologist Margaret Alice Murray was investigating the body remains of the “Two Brothers” from the Middle Kingdom (12th Dynasty, Manchester Museum mummy No. 21470, Nekht-Ankh and No. 21471 Khnum-Nakht) in an interdisciplinary approach. Later decades of mummy research focussed on single examination of new discovered mummies such as Tutankhamun (1925 by Douglas Derry and Howard Carter) and the Rulers of Tanis, Psusennes I. and Amenemopet, discovered by Pierre Montet (1939, 1940 also by Douglas Derry). Later the mummy research fell asleep until the highly important serial investigation of the royal mummies using x-ray in the late 1960ies by James E. Harris and Kent R. Weeks, published in 1973 and 1980. Another important landmark, making new standards in mummy research was the Manchester museum mummy project, published in 1979 examining several mummies with x-ray, dentistry, 14C-radiocarbon dating, experimental mummification, fingerprint examination, facial reconstruction and more.

Mummification style changes through time

Style and technique applied changed through Egyptian history. This fact makes it possible to date a mummy even if the finding context is unrecorded and any inscription and funeral equipment is absent. During Predynastic time the mummification was primarily natural by deposing the dead bodies in oval holes in the desert ground. The dead bodies were laid down in an embryo-like, but soon first attempts were made to improve the natural mummification: Viscera were taken out and a resin made of Pistacho was already in use.

Mummies from the Old Kingdom

During the Old Kingdom the dead were buried in larger tombs (Mastaba) and the Kings were placed in Pyramids. Thus the contact to the dry sand was lost and had to be replaced by a completely artificial one. The exact nature and methods of the Old Kingdom mummification is still debated. Probably natron-salt was used (either dry or as liquid). The outer appearance of the finished mummy was vitally important in this time. Sometimes the face was re-modeled with a gypsum-mask. Most mummies of the Old Kingdom are decayed to mere skeletons, only few survived as quite intact mummy. Some Royal mummies from the Old Kingdom are known, but debated, if they were authentic the remains of the Kings and Queens or later reburials from the New Kingdom or even the Late Period. Probably genuine are the following Royal remains: The mummy of King Raneferef (Radiocarbon tested and found in his Pyramid) and the mummy of Djedkare Isesi (both were Radiocarbon tested and were found in their Pyramid. We also know some Queens, such as the skeleton of Queen Mereshankh III (Found in her mastaba) and the Skeletal remains of Queen Ankhesenpepi II, recently discovered by a French Expedition in her Pyramid. Many other remains are uncertain (Unas, Seneferu) or from a later re-burial (the alleged remains of Djoser or the supposed remains of King Menkaure, dating much later than their reign). During the 4th Dynasty the first canopic containers appear. They were either stone boxes with four compartments (e.g. the canopic box of Queen Hetepheres I) or simple yet elegant stone vessels (e.g. the canopic jars of Queen Meresankh III). The use of canopics was limited to the Royal family and the top of the elite. During time the canopics became general standard and were used by a wider range of the society.

Few mummies from the Middle Kingdom

Science only has few mummies from the Middle Kingdom, while a greater number of canopic jars are known. Remains of the Kings are almost absent (few bones are in collections but uncertain). On the other hand, several mummies of Queens are known. They show a different mummification: No evisceration was performed.

Peak of Mummification during the New Kingdom

During the New Kingdom a peak of mummification technology was reached. Many mummies from this age were known and often in good condition. Many Kings and some Queens and the family of the High Priest of Amun were discovered in several secondary cachettes: the first Royal cachette Deir el-Bahari 320 was found in 1871 by Ahmed, Soliman und Mohammed Abd el-Rassul and investigated by the Antiquity service in 1881 when the secret ‘bank account’ of the tomb robber family was revealed. French Egyptologist Victor Loret (1859-1946) discovered in 1898 in the tomb KV 35 of King Amenhotep II the second cachette, holding additional Royal mummies. Later some singular burials of great importance were found: Ernesto Schiaparelli discovered putative remains of Queen Nefertari in her tomb in the Valley of the Queens (QV 66) in 1904. Theodore M. Davis found the tomb of Horemheb (KV 57) containing some human remains. Davis also found the Amarna-Cachette KV 55 holding one of the most mysterious and highly debated mummy: A man, c. 20-30 years old and closely related to King Tutankhamun. The KV 55 mummy is either identified as King Smenkhkare or King Akhenaton. Molecular genetics recently identified him as genetic father of Tutankhamun.

- Mummy of King Ramses II (19th Dynasty) Picture: G. E. Smith, Royal Mummies (1912) Copyright expired

Stuffed mummies of the 3rd Intermediate Period

While the unity of Egypt declined and Palestine was lost, the art of mummification reached a new level: The skin was stuffed to achieve a life-like appearance of the finished mummy. The viscera were taken out, were dried and wrapped and placed back in the abdomen.

- Mummy of Queen Nedjmet (21st Dynasty) Picture: G. E. Smith, Royal Mummies (1912) Copyright expired

Decline of mummification art in the Late Period and Greco-Roman time

The Saïte Renaissance (26th Dynasty) was a revival of old fashioned and traditional values and art: The canopic jars were used again as container for viscera and the mummification art had its last peak. The Greek and Roman age introduced several changes: The quality of the mummification was considerably lower; evisceration became rarer, while bitumen was used in abundance. The exterior look of the mummy was the more important factor. Beautiful wrapping, gilded funerary masks define the Greek period. The last canopic containers finally disappeared. The Roman time invented a new design: The mummy mask was replaced by a mummy portrait painted with wax-encaustic. These portraits are one the most important source of ancient painting. The hair-style and depicted jewellery makes it possible to date the mummies with good accuracy.

Molecular genetics and the new Bioarchaeology

In the last years several new technologies were successfully used in mummy research, such as CT-scan, MRI and Terahertz-Imaging will follow in near future. Egyptology is at dawn of a new Bioarchaeology, including molecular genetics: CT-Scan in 2005 revealed the leg injury of Tutankhamun, which is nowadays considered as a possible cause of death, while the murder theories, purporting a blow against the head are rejected. The first ancient DNA-extraction from a mummy was done by Svante Pääbo in 1985, but it took years to overcome the massive problem of contamination by modern DNA. A landmark in aDNA was published February 17 2010, when the results of the Tutankhamun Family Project were presented to the public: They baffled and caused a still ongoing dispute. The parents of Tutankhamun are:

- Father: The Mummy from KV 55 (Cairo CG 61075) either identified as Akhenaton or Smenchkare.

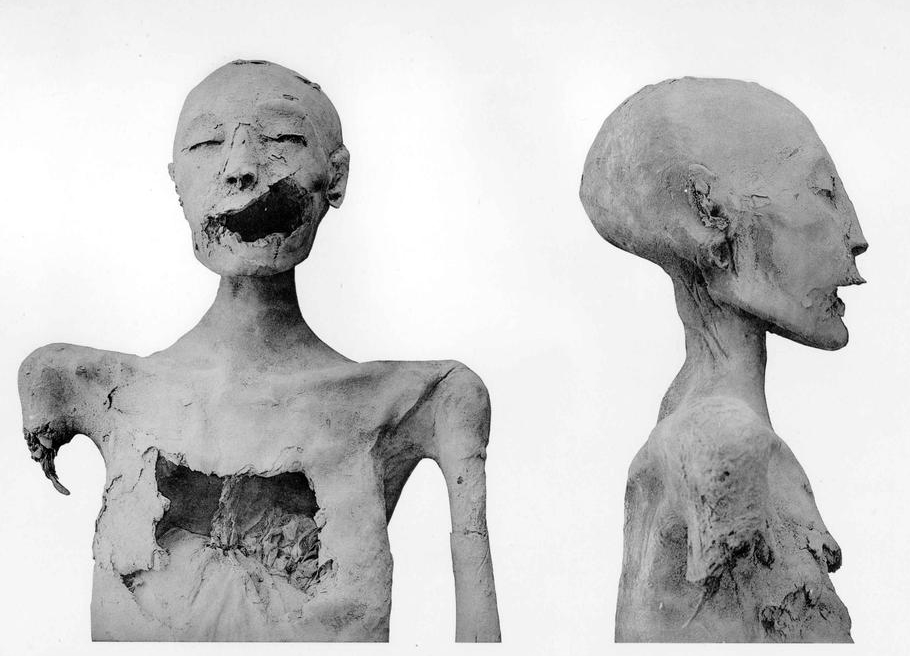

- Mother: The ‘Younger Lady’ from KV 35 (Cairo CG 61072), identified

by several scientist as Queen Nefertiti (Luban 1999, Fletcher 2003,

Habicht 2011, Schlögl 2012, Gabolde 2014, Dodson 2014).

- Mummy of the ‘Younger Lady’ from KV 35, genetic mother of Tutankhamun (18st Dynasty) Picture: G. E. Smith, Royal Mummies (1912) Copyright expired

Surprisingly the parents of Tutankhamun seem to be siblings. Their parents have also beenidentified: their father was the mummy CG 61074, found in KV 35 identified as King Amenhotep III. The mother was the ‘elder lady’ from KV 35, as genetic daughter of Juya and Tuya she is almost certain Queen Tiye. While the identification of the ancestors of Tutankhamun are still debated, new molecular research was published: The harem conspiration against Ramesses III, identifying Unknown Man E as closely related to Ramses III.

Further reading:

- Philippe Charlier et al., Genetic comparison of the head of Henri IV and the presumptive blood from Louis XVI (both Kings of France), Forensic Sci. Int. (2012).

- Zahi Hawass et al. Revisiting the harem conspiration and death of Ramesses III: anthropological, forensic, radiological, and gentic study. BMJ 2012; 345; e8268.

- Hermann A. Schlögl, Nofretete, Die Wahrheit über die schöne Königin (2012) Verlag C. H. Beck.

- Michael E. Habicht, Das Geheimnis der Amarna-Mumien, DNA-Untersuchungen klären die Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse auf, Antike Welt 6/2012, S. 21-26. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz.

- Michael E. Habicht, Nofretete und Echnaton. Das Geheimnis der Amarna-Mumien (2011). Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig.

- Zahi Hawass et al. Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s family: In: JAMA 303/7, February 2010, S. 638-647.

- Lena Öhrström, Andreas Bitzer, Markus Walter, Frank J. Rühli, Technical Note: Terahertz Imaging of Ancient Mummies and Bone, American Journal of Physical Anthropology 142: 497-500 (2010).

- Zahi Hawass, M. Shafik, Frank J. Rühli, A. Selim et al, Computed Tomographic Evaluation of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, ca. 1300 BC. ASAE 81, 2007, S. 159-173.

- Abigail S. Bouwman et al., Brief Communication: Identification of the Authentic Ancient DNA Sequence in a Human Bone Contaminated with Modern DNA. American Journeal of Physical Anthropology 131; 428-431 (2006).

- Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story (1998). Deutsche Ausgabe: Der Mordfall Tutanchamun (2000). Piper Taschenbuch, München.

- Renate Germer, Das Geheimnis der Mumien (1997). Prestel-Verlag, München.

- Pääbo, Svante, Molecular cloning of ancient Egyptian mummy DNA. In: Nature, Band 314, Nr. 6012, 1985, S. 644–645.

- Harris, James E. et al. An X-Ray Atlas of the Royal Mummies (1980). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago und London.

- Rosalie A. David (Hrsg.), The Manchester Museum Mummy Project (1979). Manchester University Press.

- James E. Harris, Kent R. Weeks, X-Raying the Pharaohs (1973). Charles Scriber’s Sons, USA.

- G. Elliot Smith, Royal Mummies (1912, reprint 2000).